Orientation 2019: Photos, Numbers, and "Atticus Finch Moments"

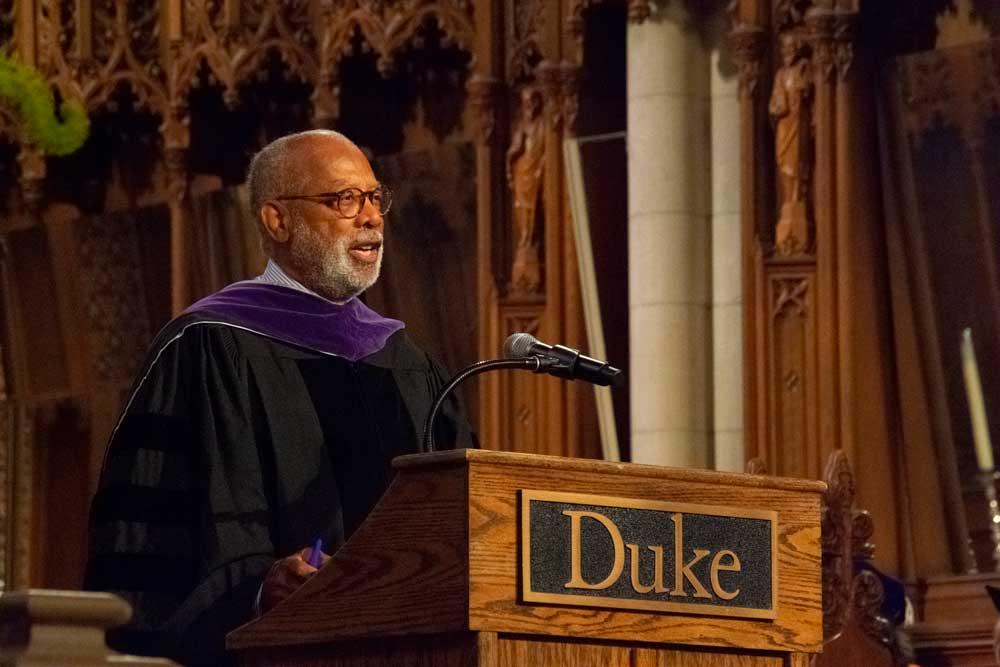

Coleman, the John S. Bradway Professor of the Practice of Law, addressed the new students during the Graduate and Professional Schools Convocation. He told the students that there is no single blueprint for a meaningful career, pointing to his own professional path, which began in private practice before shifting into academia and work with the Wrongful Convictions Clinic and the Duke Innocence Project, programs that have freed seven innocent men from prison since 2011.

Coleman called those exonerations "Atticus Finch moments," referring to the lawyer from To Kill A Mockingbird who defended a black man accused of raping a white woman. Finch, he said, is revered by lawyers for his courage and integrity.

"Each of you will face many opportunities in your careers to act with courage and integrity, sometimes against the prevailing winds," Coleman told the new students. "Whether you rise to the occasion will depend on whether you are prepared and conditioned to do the right thing. That preparation and conditioning will begin here, and will continue throughout your careers." [Read the text of Coleman's speech | Watch the convocation]

The convocation marked the official start of the new academic year. The Graduate School is welcoming the largest class in its history, totaling more than 1,000 new Ph.D. and master's students.

New Graduate School Students by the Numbers

479 | New Ph.D. students (out of 8,237 applicants) | |

555 | New master's students (out of 5,341 applicants) | |

46% | Of the new students are women | |

57% | Of the new students are international | |

52 | Countries are represented among this year's new students | |

19.4% | Of the new domestic students are from underrepresented racial/ethnic backgrounds |

Photos from Orientation Week

Text of James E. Coleman's Convocation Speech

I attended college and law school in the mid-60s and early 70s, during a period of great turmoil in the country and the world; much like the period in which we live today. Major American cities were being burned to protest racial discrimination; Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated; we were fighting an unpopular war in Southeast Asia, for which young men of my generation were being drafted and sent to fight and sometimes to die in what many thought was a senseless conflict; Nelson Mandela was still in prison; and apartheid seemed permanently entrenched in South Africa.

during Graduate and Professional School

Convocation on August 21.

In 1974, the year I graduated from law school, the country faced a constitutional crisis when the President refused to turn over audio tapes he had secretly recorded reflecting his role in the pervasive misconduct that we now call “Watergate” and the Congress was considering whether to impeach and remove him. Lawyers figured prominently in that crisis, on both sides. While I was in Detroit clerking for a federal district court judge, Richard Nixon resigned from the Presidency in disgrace.

Despite the uncertainty and anxiety of those times, many of my generation wanted to be a part of what was happening. We thought we could create a better world. Many of us became lawyers for that reason and, although we face new and different challenges today, many of us are still motivated by that belief. But the torch is being passed to new generations and other professions and soon it will be your generation’s responsibility to pursue justice and change in the midst of the gathering storms of your time. That is what your education at Duke will help prepare you to do, whatever profession you pursue.

I left the private practice of law in 1996 because I thought being a law professor was a better way for me to help prepare and motivate future generations of lawyers to assume the responsibilities that many in my generation had assumed after we left law school more than 40 years ago.

Some of you may have a notion that you need to determine while at Duke precisely how your career should unfold, that to be a successful doctor, or engineer, or lawyer, you must perform neurosurgery at major hospitals, or build tall buildings, or lead major law firms. But nothing could be further from the truth. The role of Duke’s graduate and professional schools is to prepare you to be an excellent practitioner, whatever path you follow. You can pursue justice and fairness in the world wherever your path leads.

When I left law school, I wanted to be a civil rights lawyer. But the job I wanted wasn’t available when I needed it, so I began my career at a private law firm in New York as an antitrust lawyer. When I left the private practice of law in 1996, I was a partner in a prominent Washington DC law firm, representing clients like CBS and a natural gas pipeline in Charleston, West Virginia. But between those two jobs, I also became a civil rights lawyer; from 1976-1978, I helped setup the Legal Services Corporation, which funds legal services for people who cannot afford a lawyer; In 1978, I investigated two members of Congress for corruption; In 1980, I helped to organize the new U.S. Department of Education and provided legal advice to the Office of Civil Rights, known today for its enforcement of Title IX; , and beginning in 1983, while at my law firm, I defended two inmates on Death Row in Florida, including Ted Bundy, whose execution I witnessed in 1989.

There is no single blueprint to a meaningful career. Those of you who will become lawyers can make a contribution to the public interest from the offices of a major law firm, from a government agency, or from an organization devoted to a single social issue.

My friend John Payton, who died several years ago, argued the University of Michigan affirmative case in the Supreme Court while he was a partner in a major Washington law firm; after that, he left private practice to become Counsel Director of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, a job first held by Thurgood Marshall.

John’s wife, Gay McDougall, who graduated from Yale Law School, was executive director of the South Africa Project of the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, which private law firms in New York and Washington founded in 1963 to help end apartheid in South Africa. On April 27, 1994, Gay had the honor of standing at Nelson Mandela’s side when he voted for himself to be President of a Free South Africa.

My point is that your career will evolve; what you do here and in the various jobs you take after you leave will be part of a process that will allow you to look back one day and only then determine what kind of career you had, and know that you made a difference.

Former Senator Robert F. Kennedy gave a speech in South Africa in 1966 about the challenges facing young South Africans trying to eradicate the evils of apartheid in their country. He said the students faced four dangers that would be obstacles to change in their country. I think every generation faces the same four obstacles, whether in South Africa, Hong Kong, or here in the United States:

First “the danger of futility: the belief there is nothing one man or woman can do against the enormous array of the world’s ills – against misery and ignorance, injustice and violence.”

Second is the danger of expedience: the notion that your hopes and beliefs must bend before immediate necessities. That before you can help others, you must first provide for youself by establishing your career, and only then look for ways to help others.

Third is the danger of timidity; not having the courage to withstand the disapproval of your fellow students or the censure of your colleagues, or even the wrath of your country. Senator Kennedy told the South African students that moral courage is more rare than bravery in battle or great intelligence; yet, he said, “it is the one essential, vital quality of those who seek to change the world which yields most painfully to change.”

The fourth danger that Senator Kennedy identified was comfort, “the temptation to follow the easy and familiar paths of personal ambition and financial success so grandly spread before those who have the privilege of education.”

Duke will help you to identify when these obstacles stand in the way of you making a difference in your career. We do this every day at the Law School in our clinics, our externships, and our pro bono activities. But, whether you are in the law school, or the graduate school, or some other professional school, you will be taught by faculty who themselves navigated these dangers in their own lives and helped to shoulder the responsibility of their generation by dedicating their careers to the education and training of students like you.

I once wondered why the role model for the heroic American lawyer was Atticus Finch, a fictional character in To Kill A Mockingbird. As you know, he was a lawyer in a small Southern town during the depression. Atticus Finch is revered by lawyers because he defended Tom Robinson, a black man accused of raping a white woman, at a time when mobs often bypassed the criminal justice system in such a case, in favor of the swift injustice of a rope and tree; lawyers who defended such individuals often did so at great risk to their lives and careers. Today, we would not notice Atticus Finch in such a case; nor would we think that what he did was especially heroic if done today. The story is commonplace, played out in courtrooms all around this country.

The reason we revere Atticus Finch, however, is because we judge his courage and integrity by the times and circumstances in which he acted. In that sense, each of you will face many opportunities in your careers to act with courage and integrity, sometimes against the prevailing winds. Whether you rise to the occasion will depend on whether you are prepared and conditioned to do the right thing. That preparation and conditioning will begin here, and will continue throughout your careers.

Duke is a community that promotes excellence in all we do. As part of that excellence, we stress the values of professionalism, civility, ethical conduct, and public service. These are the values we try to pass along in our teaching and mentoring and in our every day interactions.

The Duke Wrongful Convictions Clinic and Duke Innocence Project have freed seven innocent men from prison since 2011. Several years ago, when we obtained our first exoneration, the Duke Law Magazine wrote that it takes a village to do the Clinic’s work. Indeed, the Law School and the larger community that includes our alumni are such a village.

One of our most beloved former clients, LaMonte Armstrong died last week. The young lawyers who helped to free him when they were students attended his funeral yesterday. When LaMonte was exonerated in 2012, after 17 years in prison for a murder he did not commit, the team of lawyers, students and Duke alumni who had worked on his case over the years gathered in a Greensboro courtroom to witness the judge sign the order that would free our client. Before rsigning the order, however, the judge spoke directly to LaMonte:

What I wanted to tell you is judges put their pants on one leg at a time, just like you do. And every day we go to court hoping to do justice, wanting to do justice. And at the end of the day, we leave hoping that we did justice, but we never know. I believe that I do justice on a daily basis, but believing isn’t knowing.

And I was telling a colleague earlier today, probably, this is as close to knowing that I’m doing justice as I will ever experience in my career as a judge, and it makes me proud to be a judge. It makes me proud to be a lawyer. It makes me proud to be a lawyer in this judicial district where we have prosecutors and police officers [who] are committed to doing justice, and I am proud of your lawyers and those students who were at Duke, who I understand are now lawyers, and it is my sincere wish that your life will go forward in a positive manner from today.

That was an Atticus Finch moment for the law students and alumni present in the courtroom that day. In To Kill a Mockingbird, that moment comes after the all-white jury convicts Tom Robinson and Atticus Finch packs his briefcase and walks defeated toward the door. As he approached the rear of the courtroom, the black people who sat in the balcony stood to honor him. That is when Rev. Styles says to Scout, Finch’s daughter, “Jean Louise, stand up. Your father is passing.”

Duke Law students and alumni had another Atticus Finch moment this year on May 23, when a federal judge freed our client Charles Ray Finch after 43 years in prison for a murder he did not commit. Duke students first began working to free Ray in 2002. The work we do, and the work you must do to make this a more just world, is a marathon, not a sprint.

An Atticus Finch moment is not about winning; it is about showing up to try to make a difference, to be part of the struggle. It may be a lawyer helping a tenant defend against an unfair eviction, or a doctor treating an immigrant child, or an engineer working on a water project in a poor community, or a volunteer enriching the life of a child by teaching her to read and appreciate literature.

I now join others in welcoming you to this amazing community that is Duke University. And I hope life at Duke and beyond will reward you with countless moments of believing, if not knowing, that you have contributed to justice and fairness and kindness in the world. Thank you.