As Duke’s Centennial encourages a look back at the history of the university, Black History Month emphasizes the experiences and impact of Black people in local, national, and global histories. Of course, the work of preserving, uncovering, and highlighting Black history continues 12 months out of the year for those engaged in the field, as demonstrated by four Ph.D. students in Duke’s Department of History who are also pursuing the Graduate Certificate in African & African American Studies (AAAS). Read below to learn about their individual research projects, their inspirations, and their perspectives on what “Black history” signifies.

A Long-Standing Commitment to Saving Slave Houses

As a licensed preservation architect, Jobie Hill is known for her work with slave houses, a profession that she says necessitates backgrounds in many different fields. With a bachelor’s in anthropology and master’s degrees in historic preservation and art history, and after surveying hundreds of sites across eight states, Hill came to Duke to continue a long-term project with a plantation in Nelson County, Virginia.

“There are descendants of the enslaver and the enslaved community that I work with,” says Hill. “A descendant of the enslaver is the property owner. It’s in the family. And the [Massey] family has donated massive amounts of family papers to different repositories, and Duke is one of those repositories.”

Hill runs a nonprofit called Saving Slave Houses, and she regularly tries to partner with other professionals of color, highlighting “the work that they are doing together” and “the people that usually don’t get as much attention.”

And while she receives an influx of engagement requests during Black History Month, she emphasizes that the work continues year round.

“It's really about making an effort and being committed,” Hill says. “Part of that is not viewing these things as projects that have an end date, but as long-standing commitments that you're making.”

The working title of Hill’s dissertation is “Negro Woman and Her Future Issue and Increase.” She says she is most drawn to exploring unknown or lesser-known people—like a female child named Kitty, born to an enslaved woman, documented as being “lost in the woods.”

“For me, there's just a lot that's packed into that statement, right?” Hill says. “You know, what does loss mean? What does it mean to be ‘lost’ at two years old?”

Black Cemeteries and the Collective Need to Remember

Like Hill, third-year Ph.D. student Jade Marcum is committed to seeking out lost and forgotten subjects in her work.

Marcum joined Duke’s Department of History in part because of its “strong standing in Southern history,” and she originally planned to continue her undergraduate research on George Wallace, outlining his sustained attempts to stifle equal voting rights as the longtime governor of Alabama.

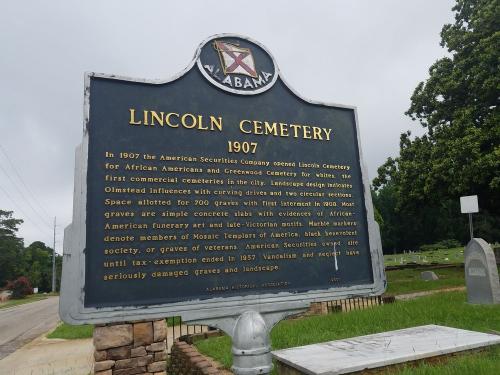

However, a visit to George Wallace’s “immaculate” grave—contrasted with the neglected state of Black cemeteries in Montgomery—motivated Marcum to change her graduate research focus.

Now, Marcum’s dissertation project tries to answer the question: “If the civil rights movement was as successful as people like to believe it was, why are we still so severely segregated in death? And why are Black cemeteries still receiving less funding and less care?”

In keeping with her research interests, Marcum is the Teaching Assistant for a class called Human Rights Durham: Mapping Maplewood Cemetery, taught by Professor Robin Kirk. Marcum will lead a session on the challenges of writing Black history, and she looks forward to asking students what they think makes Black history special or worth doing. For Marcum, the impetus is as personal as it is academic.

“I am Black, I grew up in Montgomery (the area I study), and my family has lived there for as long as I can remember,” says Marcum. “I had a family member pass recently, and I knew that despite everything, she was going to be buried in what is basically a segregated cemetery in 2023.”

“I think that there needs to be a drastic shift in education today—even at the collegiate level, even at Duke—towards treating the liberal arts and history as legitimate fields that people need to learn about,” Marcum adds.

According to Marcum, this shift would include recognizing that “African American history is US history” and that these stories should matter to everyone.

Broadening Black History in Today’s Political Landscape

For Tayzhaun Glover, who is currently writing a dissertation on the eastern Caribbean, colonialism, and slave flight/fugitivity, Black History Month has changed over time and continues to broaden its horizons.

“I think that Black History Month very much began as more of a US-centered understanding of Blackness and what it means to be African American,” Glover says. “But I think that the conversation has evolved towards more of a global approach to understanding Blackness and the Black diaspora.”

Like Hill and Marcum, Glover sees Black history as part of and integral to wider histories, just as the Black experience itself encompasses a wealth of different perspectives that need to be discussed and understood—for example, Black women’s experiences and the Black LGBTQ+ experience.

“There is increasing interest in Black history outside of just Black people,” Glover adds. “And especially now—at a time where, for political reasons, Black history is explicitly undervalued or endangered—this is a very critical moment that we live in.”

It is fitting that one of Glover’s favorite thinkers is Henry Louis Gates, Jr., a longtime public historian known for his pioneering insights into African American culture and literature and for a current PBS show Finding Your Roots.

But Glover is equally inspired by his South Carolinian grandfather, who has shared bits of his own history working as a sharecropper and living under Jim Crow laws.

“He can tell you so many things, like how he felt as a kid or how he has seen certain things evolve as he's gotten older. He really is kind of doing the work of a historian,” says Glover. “I think about him a lot when I'm writing or trying to turn these fragmented sources into a narrative, sort of thinking, ‘What would this person have thought about or how would they have framed this experience on paper?’”

"When and Where I Enter”: Black Women’s History

Fifth-year Ph.D. candidate Reina Henderson is likewise researching the eastern Caribbean islands with an emphasis on Black perspectives, and she is pursuing a Graduate Certificate in Latin American and Caribbean Studies in addition to the certificate in AAAS.

“It's giving me the chance to not get so bogged down in a traditional history approach, and to pull from different schools of thought,” says Henderson. “People of African descent tend to be left out of sources that are in the archives or are relegated to a line here, a line there. Having multiple tools at my disposal has been essential to recovering as much as I can of those perspectives.”

Her ability to read in English, French, and Haitian Kreyòl are especially helpful in gathering as much information as possible from various sources. She looks forward to a research trip to the Caribbean island of Martinique in March 2024.

Like Glover, Henderson has been significantly influenced by her grandfather—though indirectly, through stories shared by her father.

“I never got to meet my grandfather,” says Henderson. “But from stories my dad tells me of him, he was that person in the community who knew something about everything. He had the full collection of encyclopedias and would just read for hours on end. He taught that to my dad, and my dad taught that to me.”

Henderson says that her father loves hearing stories about her research and has even helped her “come up with a title or two for this or that chapter or paper.”

But in addition to this familial legacy, Henderson is spurred on by the work of Black women—especially Anna Julia Cooper, whom she considers “the godmother of not only Black feminism, but also Black female historians.”

Henderson has the following Anna Julia Cooper quote up on her wall: “Only the BLACK WOMAN can say, ‘When and where I enter, in the quiet, undisputed dignity of my womanhood, without violence and without suing or special patronage, then and there the whole Negro race enters with me.’”

The Graduate School Celebrates Black History Month

For more on Black history—and for Black history as it intersects with The Graduate School, specifically—check out our social media channels for an ongoing campaign drawn from our online TGS timeline.