As The Graduate School celebrates its 90th anniversary in 2016, we are taking a look at various aspects of the school’s history. Visit https://gradschool.duke.edu/90 for more information about the 90th anniversary celebration, as well as other Graduate School history spotlights as they are published.

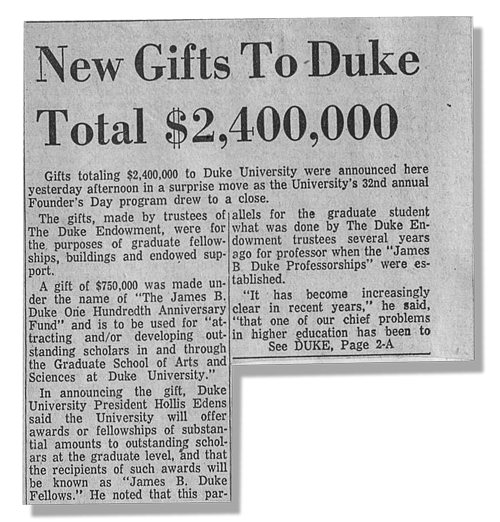

gift that created the James B. Duke

Fellowship.

When Duke commemorated what would have been James B. Duke’s 100th birthday on Founders’ Day in 1956, The Duke Endowment made a surprise gift to the university—an endowment that created the prestigious James B. Duke Fellowship for doctoral students. In the 60 years since its creation, the JBD Fellowship has supported hundreds of Duke graduate students. Here’s a look at one student from each of those six decades:

- 1960s: Michael Bassett, Ph.D.’64, History

- 1970s: Dian Fox, A.M.’77, Romance Studies; Ph.D.’79, Romance Studies

- 1980s: Clarence Newsome, ’72, Religion; M.Div.’75; Ph.D.’82, Religion

- 1990s: Tomiko Brown-Nagin, A.M.’93, History; Ph.D.’02, History

- 2000s: Audrey Ellerbee Ph.D.’07, Biomedical Engineering

- 2010s: Chris Paul, ’05, Environmental Science; Ph.D.’16, Environmental Policy

1960s: Michael Bassett

PH.D.’64, HISTORY

More than 50 years ago, Michael Bassett hopped on a ship in his native New Zealand and sailed 24 days across the Pacific Ocean, through the Panama Canal, to the port of Miami. From there, he took a Greyhound bus to Durham, where, to his great surprise, the bus station was segregated.

“It was startling coming into the Durham bus terminal to see black people in these little, wee, cramped facilities, and the whites in an almost empty, large lounge,” Bassett said. “Between 1961 and ’64, the big desegregation program was taking place at a fantastic rate. It was so visible and so immediate, and the newspapers were full of it and our conversations were full of it. It was pretty electric stuff.”

In 1961, Bassett had just earned a master’s degree at the University of Auckland in his hometown and was preparing to study history at Duke at The Graduate School. He had applied to the London School of Economics and Stanford University, but neither institution offered adequate financial support. With dreams of teaching at the university level and his widowed mother unable to continue to support his graduate education, he was on his own.

To his great good fortune, Bassett received the James B. Duke Fellowship, which had been established just five years earlier. The grant was worth $3,000 per year, paid in monthly installments September through May. During the summer, Bassett did work study for the chair of the history department, for which he was paid $300.

Studying American history during an important time in American history, Bassett thrived at Duke. Since his undergraduate days, he had a strong interest in politics and a notion that he would serve in government in New Zealand. Bassett wrote his dissertation on the Decline of Socialism in America, turned it in on November 21, 1963—the day before John F. Kennedy was assassinated—and again found himself neck deep in seminal historical events.

A university teaching position awaited him in New Zealand, so there was some urgency to get back home—despite the fact that the entire nation was transfixed as President Kennedy’s assassination played out on television. His dissertation defense took place the day after JFK’s funeral. “I had the dubious distinction of having had an oral exam where almost nobody except for my supervisor had read my 300-page thesis,” Basset said. “Someone asked about the intro and chapter one, and I think the highest page number for which I received a question was page 30.”

Granted his Ph.D., Bassett arrived back at his alma mater just in time to become a leader in the burgeoning field of American studies. He taught American history for almost a decade and was involved with a biennial Australia-New Zealand American studies conference starting in 1965.

Bassett actually answered the siren song of politics just a couple of years after returning home to teach, but was figuratively smashed on the rocks. Running as a candidate in the Labour Party, he lost two elections for Parliamentary seats before winning a seat in 1972—and losing it again in 1975. He was re-elected in 1978 and held the seat until he retired from politics in 1990.

During the latter half of his political career, Bassett served two terms in the cabinet of prime ministers Geoffrey Palmer and David Lange, whose Fourth Labour government led the most significant reforms in modern New Zealand history. New Zealand was in crisis in 1984, with runaway inflation, crippling debt, and bloated government programs. With Bassett at his side in cabinet positions from Minister of Health to Minister of Local Government, Lange and his crew passed a dizzying array of laws to restructure the economy, streamline services, and allow more social freedoms, all in such a way that their reforms would solve the problems permanently.

Anne Firor Scott, then the chair of the Duke history department, visited New Zealand in 1984 and met with all of the Duke graduates in the country, including cabinet member Bassett; John Henderson, the prime minister’s chief of staff; Graham Scott, the secretary of the treasury; and Otago University historian Erik Olssen, all of whom had been James B. Duke fellows.

“The people that Duke took in on a variety of scholarships benefited hugely,” Bassett said. “I think you can infer that generous funding for people showing some ability in countries like New Zealand can have a very big impact on a particular country.”

Bassett never really left government, turning to his training as a historian to write 12 books about New Zealand politics. In the process, he became the country’s preeminent political historian. His latest book project is a comparative study of all 24 prime ministers of New Zealand.

Bassett even had an opportunity to help bridge racial divides New Zealand. In 1994, Bassett was appointed to the Waitangi Tribunal, a group that hears land grievances from the native Maoris. He served 10 years on the tribunal, indulging a passion that sparked on his very first day in Durham.

“Throughout my entire career, my American experience, thanks to Duke, was enormously important to me, particularly in race relations.”

1970s: Dian Fox

A.M.’77, ROMANCE STUDIES; PH.D.’79, ROMANCE STUDIES

Dian Fox has been thinking a lot about Hercules lately. Fox, a scholar of Renaissance Spanish literature, is studying icons of masculinity in drama, and there are few icons more masculine than Hercules. Most of his famed 12 labors involved superhuman strength. Over the centuries, perhaps because some of Hercules’ labors took place on the Iberian Peninsula, the mythical hero was co-opted as a native son of Spain. He appears prominently in Renaissance paintings, statues, and literature, of course.

Fox had been teaching about Renaissance Spanish literature for years when the birth of her daughter began to change the way she approached her life and her work. “I became a lot more aware of the impact of gender on people’s lives, and especially on my daughter’s life and my own,” Fox said. “That opened my eyes and made me very curious.”

Gradually, the gender component became more important to her work at Brandeis University, where she has worked for nearly 30 years. Fox realized that her research was relevant to what was then called women’s studies, and soon she was invited to join the department. This is how her title became Professor of Hispanic Studies and Women's, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, and why she is studying the presence of Hercules in 400-year-old writings.

“I was interested in the ways one’s gender limits possibilities but also opens up possibilities,” Fox said. “I became drawn to performances of masculinity and ways that social expectations weigh also on men. And in patriarchy, men oppress women, but men also oppress other men. That was really, really important to me. I felt a real empathy for the male characters in the plays that I hadn’t felt before.”

It was the James B. Duke Fellowship that launched Fox into the world of academia. After finishing her undergraduate degree at the University of Oregon, she wanted to continue enjoying literature, writing, and researching at a university, and she wanted to venture far from the Pacific Northwest, where she had spent her whole life. Fox applied to The Graduate School at Duke for its excellent Romance Studies department, and was awarded the fellowship.

“When I got the letter telling me that Duke was offering me this, I showed it to my professor and he said, ‘Now that’s a plum,’ ” she said. “And he said, ‘Take it.’ I just couldn’t believe it. I had worked my way through college. I had dropped out, saved up money, and gone back. Finally, I was going to be able to spend my time focusing on what I really loved.”

Fox found a mentor in Duke’s noted Spanish literature scholar Bruce Wardropper, who was a careful, meticulous, tough reader of her papers. Sometimes he would mark up an essay and include a page of single-spaced typed comments with it. Fox said that while it was difficult, the intense scrutiny made her a better writer and helped form her into an equally careful reviewer of her students’ work.

The James B. Duke Fellowship not only brought Fox to Durham and to her mentor, it sent her to Spain for the first time. Her third year, with coursework finished, she spent a semester in Madrid doing research at the national library every day and traveling on weekends. “That was transformative for me,” Fox said.

She experienced a second transformation in the 1990s when she began applying her newfound lens of gender to literature that she was already intimately familiar with.

“I went back to the plays I had been working on and I saw them in a whole new light,” Fox said. “It really changed my way of reading and writing about this literature and about the cultural and social conditions during that time. And, it deepened my appreciation of the need for social change in our own times, for ourselves and for future generations.”

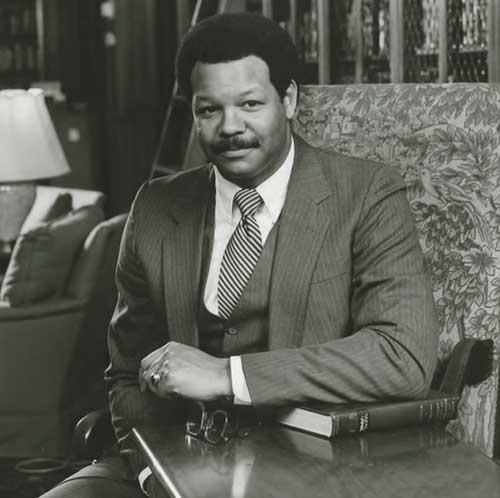

1980s: Clarence Newsome

’72, RELIGION; M.DIV.’75; PH.D.’82, RELIGION

For Clarence Newsome, receiving the James B. Duke Fellowship was an early landmark achievement in a life of landmark achievements. Newsome was a Duke football player who graduated early; the first black undergraduate to represent his class by giving the commencement address; a Divinity master’s student who helped Duke president Terry Sanford campaign for the presidency of the United States; and a Divinity doctoral student who was unanimously invited to join the school’s faculty before he completed his Ph.D. And that was all before he began a distinguished career as a university professor, dean, and president, and a lifelong champion of freedom.

Newsome fell in love with Duke as a 13-year-old in the small northeastern North Carolina town of Ahoskie. In the mid-1960s, with racial integration still a battleground statewide, he didn’t dare dream that he could attend the university. But Newsome was an outstanding athlete and an even better student. As integration progressed, he was just the type of focused, academically talented student-athlete Duke was looking for. The university recruited him to play football and, to use a football metaphor, he took the ball and ran with it.

“I never really, really wanted to go to any other school,” he said. “From the day that I enrolled, I just felt that I had to do what I could to take full advantage of my opportunity.”

It didn’t take long before the Duke community began to feel the warm affection for Newsome that he long felt for the university. Duke’s 1970 football team finished second in the Atlantic Coast Conference, and his senior season of 1971 the Blue Devils were ranked in the top 25 nationally, eventually finishing third in the conference.

Newsome graduated a semester early and immediately began work on his master of divinity degree. But it was only weeks later that he was summoned, somewhat mysteriously, to Sanford’s office. When Newsome walked in, Sanford gave him an assignment: review the strategic plan of Howard University, critique it, and brief Sanford on it to prepare him for an upcoming meeting of the Howard board that Sanford served on.

“He never asked me if I could or if I wanted to,” Newsome said. “He simply put the strategic plan in my hand, told me the date that he wanted it, and said to me that he wanted me to serve as a student assistant.”

Newsome’s work with Sanford continued for years and included helping Sanford campaign for the Democratic nomination for president in 1972 and serving as the acting dean of Duke’s Office of Black Affairs (now the Center for Multicultural Affairs). He credits this apprenticeship with helping him prepare to be an administrator.

“I didn’t have time to doubt,” Newsome said. “His confidence became my confidence, and I just sat down and did it.”

When the bulk of his work with Sanford was complete in 1974—the president still called on him from time to time over the next 11 years—Newsome rejoined his Divinity class and graduated on schedule with high honors. He considered pursuing doctoral studies at Harvard and Yale, but his close relationship with religion mentors on the Duke faculty had him leaning toward staying in Durham. Winning the James B. Duke Fellowship made it an easy decision.

It was also a good decision. With the support of the fellowship. Newsome continued his superior scholarly work. “My studies at Duke positioned me to really tap my potential and come to a level of self-understanding as to my intellectual and scholarly abilities and capacities,” he said. “I was able to do start doing some seminal thinking.”

After reading one of his papers at a meeting of the Divinity School faculty in 1982, he was invited to join the faculty. Divinity dean Tom Langford told Newsome that it was the only time in his career that such a vote was unanimous. “It was a tremendous vote of confidence,” Newsome said.

He was a member of the Duke Divinity School faculty for eight years before moving to Howard University, where he became dean of the divinity school. In 2003 Newsome was named president of Shaw University in Raleigh and led that institution for six years. He joined the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center in Cincinnati as president in 2013 and finds that the center’s mission is a continuation of his career-long focus on freedom and liberation.

Newsome’s job at the center, which features an onsite museum and large-scale educational efforts for children and adults, is to help redefine the notion of freedom internationally. He says that freedom has often meant that a small number of people are free at the expense of large numbers of other people.

“To make good on the language of the founding fathers, we’re speaking of the next step in the understanding and practice of freedom, that we call ‘inclusive freedom,’” he said. “All people everywhere enjoying rights and privileges of equal number, equal kind, and equal quality.”

Incremental steps in freedom in the United States through desegregation in the 1960s meant that the young Clarence Newsome who loved Duke could actually attend Duke by the late 1960s.

“I have felt from the first day of enrollment a deep, deep sense of obligation and even passion to express my thanks tangibly,” he said.

Newsome joked that his career track as a religion professor and academic administrator meant that he would never have large sums of money to donate to Duke, but he could always donate his time in service to the university alumni association, the football team, the Divinity School board of visitors, and the Board of Trustees, where he has been a member since 2002.

“It still amazes me that I entered Duke with the opportunity to wear a Duke blue and white football uniform, and eventually found my way to wearing a Duke trustee robe,” he said. “Every time I put that robe on, I take a minute to say thank you to God, and then to remind myself that an obligation comes with the opportunity to serve the students, the faculty, and the administration to the best of my ability.”

1990s: Tomiko Brown-Nagin

A.M.’93, HISTORY; PH.D.’02, HISTORY

Tomiko Brown-Nagin has become one of America’s foremost sociolegal historians, but it was a Duke mentor’s kindness and the freedom afforded to her by the James B. Duke Fellowship that marked her doctoral work in history and gave wings to her ascension to the heights of academia.

“The fellowship made the decision to attend Duke inevitable,” Brown-Nagin said. “Duke really wanted me to attend and was uniquely committed to my education. My time at The Graduate School ended up being one of the best times of my life. Because of the fellowship’s support, I had extra time to read, think, and write.”

Now the Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law and a Professor of History at Harvard University, Brown-Nagin has written extensively about the civil rights era. Her 2011 book “Courage to Dissent: Atlanta and the Long History of the Civil Rights Movement” won the Bancroft Prize awarded by Columbia University for works demonstrating the powerful impact of re-examination of historical events.

In the acknowledgements, she thanks longtime Duke historian (now professor emeritus) William Chafe for deeply influencing her studies and her methodology. Chafe taught Brown-Nagin the methods of a social historian, to appreciate the role of place in history, and the importance of grassroots historical actors. In her book, she united those lessons learned at Duke with legal history methods in ways that resonated with readers.

“Bill taught me that one could maintain one’s humanity even as one moved up in the academic hierarchy,” Brown-Nagin said. “He was one of the kindest people I have ever met, and partly because of the example that he set, I now aspire to show my students the same kindness that he showed me.”

She is working on two major projects: The first is a biography of Constance Baker Motley (1921-2005), the trailblazing lawyer, politician, and judge. Thurgood Marshall’s protégée, Motley was the first female lawyer at the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the first black woman appointed to the federal judiciary. “Her life and times tell us much about changing gender relations in America and in the civil rights movement, and about the efficacy of law as a tool of social change,” Brown-Nagin said.

Brown-Nagin’s other project argues that in today's hypercompetive admissions environment, selective institutions of higher education are obligated to ensure access for talented first-generation and economically disadvantaged college students. She has written that more undergraduate financial aid should be targeted to first-generation students.

“Most universities have not made recruitment of them a priority and do not keep records about them,” she said, acknowledging Duke’s efforts to support first-generation students but wanting the university to go further. “I would like to see Duke make the recruitment of first-generation students a priority.”

Brown-Nagin joined The Graduate School Board of Visitors in 2012 and said that she in enjoying learning about the school’s needs while helping Dean Paula McClain implement her vision. “Because of my terrific experience at Duke, I wanted to give back to the university,” she said. “The BOV is my way of doing that.”

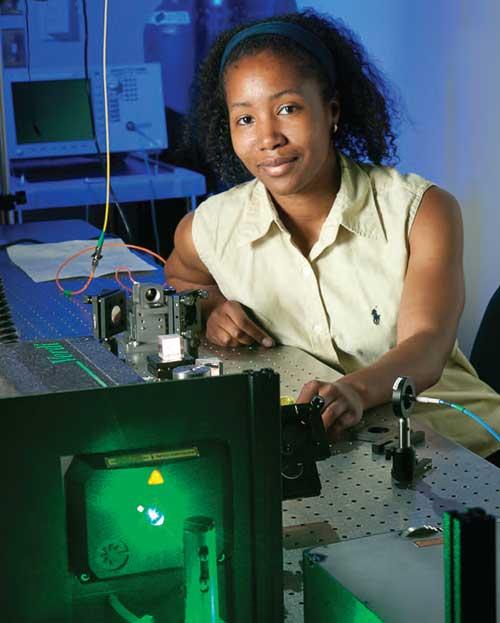

2000s: Audrey Ellerbee

PH.D.’07, BIOMEDICAL ENGINEERING

Audrey Ellerbee has a talent for seeing inside of things and situations to diagnose the best course of action. When she was comparing biomedical engineering programs for her doctoral work, Duke’s highly ranked program was on the short list. But the factors that gave it the edge were not apparent without a good, close look.

“I remember when I visited Duke’s campus, thinking, ‘Wow, the students here seem really happy,’ which was something I did not necessarily notice at other schools,” Ellerbee said. “The idea that I could have a very full and fun life as a graduate student attracted me to Duke.”

Don’t think that Ellerbee wasn’t a 100 percent serious graduate student. She was a shining star who was named Graduate Student of the Year by the National Society of Black Engineers in 2007 and served as president of the Graduate and Professional Student Council. But her vision for what she wanted in her graduate studies was holistic. Even though most of her funding came from a National Science Foundation grant, the James B. Duke Fellowship played a vital role in that vision.

“The James B. Duke Fellowship was unique because it wasn’t just a fellowship you got money for; there was an expectation that you were part of a cohort of people who were also fellows, and there was an organization around that fellowship,” Ellerbee said of the Society of Duke Fellows. “The community aspect—being integrated into a scholars’ community, was also attractive. Those scholarships were given across a broad range of disciplines, so the fellows program was inherently interdisciplinary and allowed mixing with people who were studying all sorts of things.”

While Ellerbee’s involvement in leading and networking with fellow graduate students was always intended to broaden her perspectives, it worked out even better than she planned. A graduate student’s work is spent in the lab doing research. In her current role as an assistant professor at Stanford University running the Stanford Biomedical Optics lab, which studies optical coherence tomography (OCT) for medical imaging, she spends minimal time at the bench and most of her time guiding her research program and training students. Her broad experience at Duke helped teach her skills to be an effective faculty member.

“The thing I do the least of now is the thing I did the most of in graduate school—actually being in the lab doing the research myself,” Ellerbee said. “My experience at Duke really did prepare me to serve in this role, but if I didn’t take the time to step out of the day-to-day lab work I was there to do as a graduate student, I’m not sure I would have had the same kind of preparation, perspective, and feeling of readiness for this job.”

The Ellerbee lab’s OCT work includes improving both hardware and software for the technology, which uses reflected infrared light to reveal fine detail within the body. Imaging for ophthalmology, dermatology, cardiology, and gastroenterology are common uses for OCT, which is completely noninvasive. Ellerbee is working on building systems with faster imaging and more detail, especially for early diagnosis of skin and bladder cancers.

Even with this important work going on, Ellerbee still makes time to help worthy causes. She was tapped to chair the Academic Research Symposium, a group that seeks to recruit more minority faculty into engineering. Perhaps her great vision will help find some of the next generation of star biomedical engineers.

2010s: Chris Paul

’05, ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE; PH.D.’16, ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY

“I tend to be the happiest when I’m the busiest,” said Chris Paul—and he must have been one deliriously happy guy during his time as a graduate student at Duke. In addition to working on his dissertation, he raised two young girls and was endlessly active in a variety of graduate student organizations.

Paul’s amalgam of academic interests would be difficult to pursue at an institution that was not as highly interdisciplinary as Duke. In fact, his combination of disciplines—environmental policy, political science, and global health—were such a new mix that he was part of Duke’s first cohort of doctoral students studying it.

“I’m trained as a political scientist,” said Paul, now an assistant professor of public administration at North Carolina Central University. “I tend to call myself a political economist because I’m interested in how people and households make decisions about their well-being.”

Paul’s research focuses on how humans relate to their natural environment, how the environment in turn affects their health, and how the economy and government policies influence how people take care of their environment.

It’s serious work—climate change, air pollution, lead poisoning, water concerns—and necessary to address some of the environmental issues that affect people in both developing and developed nations. So while Paul’s research covers several disciplines, it is often focused on a very specific human-environmental interaction in a specific place.

His dissertation was part of a project on water, health, and climate change in the Ethiopian Rift Valley—a collaboration between the Nicholas School of the Environment, the Sanford School of Public Policy, and the Duke Global Health Initiative. The project was funded by the provost’s office and a grant from the United States Agency for International Development. Paul was part of a team that spent two months per year in 2012, 2013, and 2014 visiting rural villages in an Ethiopian lake basin, collecting longitudinal data from 400 households.

Among other issues, the team studied where people chose to get their household water; the basic health and nutritional status of household members; and health effects related to groundwater quality, availability, and hygiene. They asked how people store water and how they cope when it is unavailable or hazardous. Finally, health-care professionals conducted basic health assessments on adults and children, evaluating for symptoms related to arsenic exposure, chronic fluoride exposure, and diarrheal disease prevalence. Paul’s dissertation included three papers looking at different angles of the research through the lens of climate change: how households adapt, how the Ethiopian government adapts, and how environmental health is affected.

Paul said the James B. Duke Fellowship made a difference by allowing him to pursue professional development opportunities that help his research, such as a summer statistics training program in Michigan. “Having the support of a program that allows me think forward about professional development and gives me the financial flexibility and institutional opportunities for that professional development was very important,” he said.

For Paul, his many volunteer and family activities served a similar function for the other side of his life. Chairing the Society of Duke Fellows, or serving on the Graduate Board of Visitors, or leading the Duke GradParents organization for grad students with children—it paralleled the obligations and aspirations of his academic work. It was professional development for life, not work.

Perhaps a sociology grad student could study Paul to see how he did it. “As crazy as it can be, it’s really fun,” he said.

— Profiles adapted from A Report from Duke University to the Duke Endowment: 2014 Buildings & Endowments