Blog

Mapping History in a Pandemic: An Unexpected Journey

At the beginning of summer 2020, my future looked uncertain. I was a brand-new Ph.D. candidate, having completed my preliminary exams in late April. My dissertation prospectus, which I was revising as borders closed around the world, outlined a project that required on-site archival research in multiple countries across two continents. And yet, due to the rapidly worsening pandemic, I was now grounded in the United States with no idea when it would once again be safe to travel internationally.

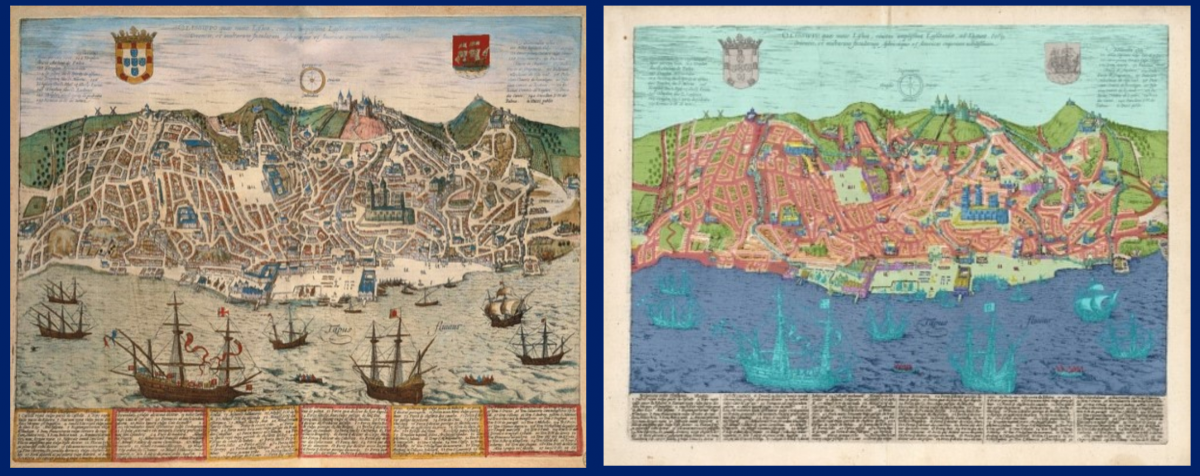

Aware of this less-than-ideal situation, my advisor, Professor Philip Stern, reached out to me with an opportunity: Would I like to participate in the preparation for a digital humanities Bass Connections project that he would be co-directing with Professor Edward Triplett from the Art, Art History, and Visual Studies department? In this project, Mapping History: Seeing Premodern Cartography through GIS and Game Engines, the students would explore how 3D modeling software could be used to visualize urban views from the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries in a way that accurately reflected premodern conceptions of space. The project would blend rigorous research in the fields of early modern cartography and urban history with the insights of interactive data visualization programs such as ArcGIS and Houdini (learn more about the groundbreaking methodology). I agreed to come on the project just for the summer, in case international travel became possible later in the fall.

Eleven months later, I met with my students for the final time as they put the final touches on their research. Participating in Bass Connections was by far one of the best professional development experiences I’ve had at Duke. Most significantly, the project has constituted deeply formative teaching experience that I wouldn’t have otherwise received if this year had originally gone as planned.

How to Plan a Collaborative, Project-Based Course?

The central ethos of Bass Connections is the value of project-based pedagogy, and working on Mapping History has provided the most effective crash course in this teaching approach. (It has also been a crash course in online teaching techniques, as every part of this project was conducted via Microsoft Teams.) I quickly discovered that planning a project-based research course posed significant logistical challenges in a way that a more traditional course does not. But the result was a stimulating yet supportive online classroom experience that enabled my students to fully take ownership over their work. As a Bass Connections project manager, I learned how to handle the particular demands of a research course by following three key steps.

Step 1. Plan Time and Space for Experimentation

From the very beginning of this project, our leadership team had to figure out a way to balance the goal of a productive final output while simultaneously allowing enough time for the students to experiment with the new research methods they were learning. We even had to allow them to fail a little before trying again. In Mapping History, we approached this challenge by planning the first semester as a kind of methodological buffet, where the students sampled different research techniques (both “traditional” and digital). In the spring, they worked in specialized sub-teams according to different methodological modes of their preference (3D modeling, historical research, etc.).

Step 2. Be Flexible With Your Research Goals

During the fall term, the project managers found that we were constantly adjusting our end-of-semester research targets. The students often needed more time than we anticipated to practice their digital annotation in Supervisely (a data labeling platform) or identify key sites in various eighteenth-century cities using resources from Duke Libraries. We had set ambitious research goals based on processing complex and occasionally obscure data, and we had to figure out a way to make those goals achievable for our students without sacrificing the methodological standards of the project.

Step 3. Trust Your Students

The answer to this challenge lay in trusting our students to overcome challenges with the project on their own terms. In planning out the spring semester, I consciously incorporated time for my students to encounter difficulties in their research and made space for us as a group to talk about them. During our weekly meetings, they shared their successes with one another as well questions and concerns, an exercise that allowed them to learn from one another’s distinct research experiences. I found that this approach actually energized and liberated the students in their work. They felt free to dive down research rabbit holes and pursue paths of inquiry that they themselves had determined were especially relevant to the overall project. In turn, this freedom helped them to refine their critical intuition and analytical skills, and they all became better researchers and better academic collaborators. This method of teaching has had a profound and lasting impact on my pedagogy.

Ultimately, my experience with Bass Connections constitutes a key moment in my nascent teaching career as well as the brightest silver lining during a period of unimaginable anxiety and stress. I have spent the past year teaching a group of bright, engaging, and deeply dedicated students, working alongside a creative and infinitely supportive project management team of faculty and fellow graduate students. Although the delay of my dissertation research abroad has been gutting, and much remains uncertain, I couldn’t have asked for a better way to spend an unexpected year in Durham.

Author

Helen Shears

Ph.D. candidate, History

Helen Shears is a fourth-year Ph.D. candidate in the History Department at Duke. She studies diplomacy and international law, specifically the process of treaty-making, within the context of European empire-building in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Before Helen returned to school as a student, she worked in international education.