Blog

Alumni Profiles Series: Michael Battle

Michael Battle received his Ph.D. in Religion with a focus on Theology and Ethics from Duke in 1995. He is an Episcopal priest, professor, author, speaker, retreat leader, and biographer of the late Nobel Peace Prize winner Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Battle has held a number of academic posts, teaching spiritual theology, moral theology, and black church studies at Duke Divinity School and the University of the South (now known as Sewanee: The University of the South). He is currently Herbert Thompson Professor of Church and Society and Director of the Desmond Tutu Center at General Theological Seminary, New York. His new book is Desmond Tutu: A Spiritual Biography of South Africa’s Confessor.

Let’s jump right in. How did you decide to make Desmond Tutu the focus of your dissertation?

I had the privilege to have Stanley Hauerwas as my supervisor. When I came to Duke, not knowing exactly what I was going to focus on for my Ph.D., I was thinking of focusing my research on Kenneth Kirk, the Oxford bishop with the beautiful moral theology that you have to have a vision of God before you can do any kind of theory of ethics, especially for Christian ethics. The more I thought about it, in doing a Ph.D. you really need to figure out a niche; the research needs to be cutting-edge in some way. And the more I meditated on that, I realized that these European bishops have had so much done on them in the past, and I thought about Desmond Tutu.

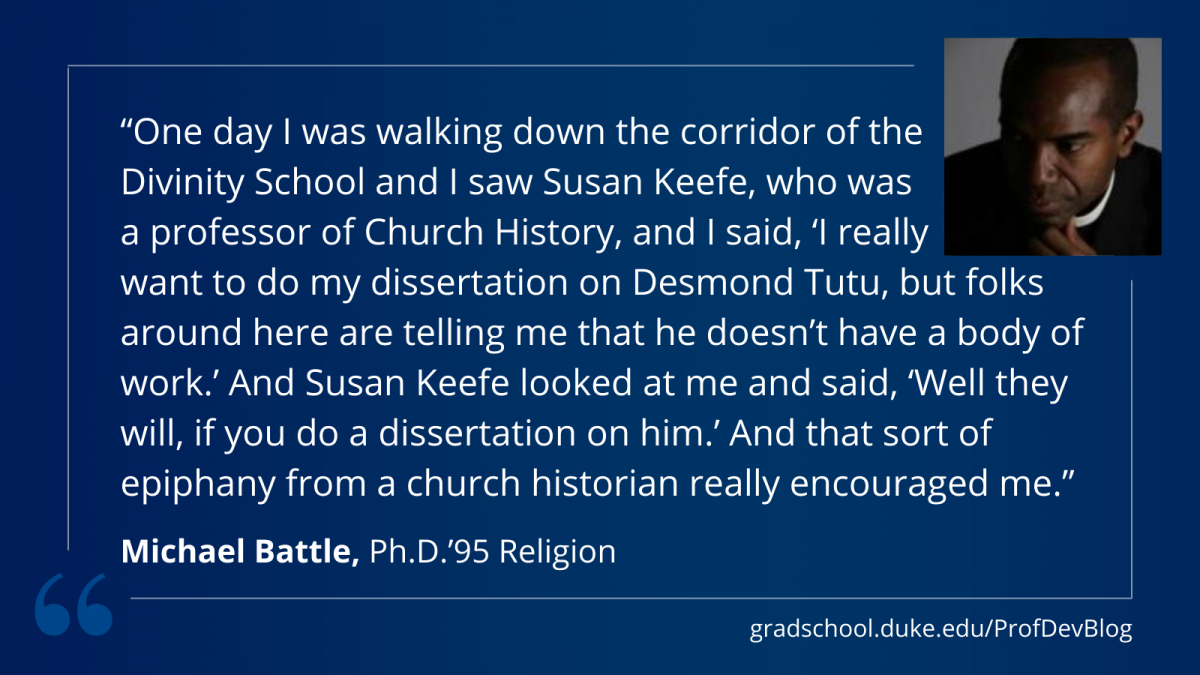

One day I was walking down the corridor of the Divinity School and I saw Susan Keefe, who was a professor of Church History, and I said, “I really want to do my dissertation on Desmond Tutu, but folks around here are telling me that he doesn’t have a body of work.” And Susan Keefe looked at me and said, “Well they will, if you do a dissertation on him.” And that sort of epiphany from a church historian really encouraged me. And of course having someone like Stanley, who had my back, that’s how I came into the dissertation.

Tell us a bit more about your time living and working with Desmond Tutu.

In 1992 Tutu, providentially, was only six hours away at Emory University – he was on sabbatical. So I drove down there with my hat in my hand, asking his permission to come to South Africa. I had no intention of living with him, just to go and have access to his papers, and maybe interview people. And when I went in his office, the first thing he said was, “Let us pray.” And then it moved from doing academic work to doing more vocational work. And he expanded the scale of how I was seeing all of this.

When I did go over in 1993, I was just walking over to his office for a couple of hours a day. This was the first two weeks. And then Chris Hani, a major South African leader, leader of the Communist party, was assassinated. Intentional things were being done to sabotage the real election. It was a fragile time in South Africa’s history. And then Tutu and his wife, Mama Leah, came and picked me up, and he said he was going to invite me over to live with him. At that time, Bishopscourt was in between chaplains, so I lived in the chaplain’s quarters for the archbishop of the province of Southern Africa, in a beautiful compound campus. I did all the things that a chaplain would do with the archbishop. And the first thing I did was stand side by side with Tutu in his march to keep peace in the midst of this assassination of Chris Hani. So it was a baptism by fire.

As a biographer, how do you understand the relationship between Tutu’s work for the rights of women and the LGBTQ community and the context of the African church?

I think Tutu would say those are two aspects of his vocational work that he wanted to do more on—in terms of encouraging women in terms of hierarchy and the power of the church, and also for the LGBTQ community to be fully understood as human beings. That’s very much his worldview of Ubuntu, to try to help us understand what it means to be human. I think the work also was for Tutu to try to be the face and voice representative of the nation-state. And I think in many ways, most of his focus, most of the demand of his energies and attention, especially as the chair of the TRC [Truth and Reconciliation Commission], he focused mostly on race and on the nation-state not becoming embroiled in the cycles of violence, especially between black and white people. I think that’s one of the reasons he stayed in that sort of worldview and leadership. He did advocate for women and for the LGBTQ community, but he would be one of the first ones to admit that he wished he could have done more.

You are a Six Preacher, which is a huge honor. Can you explain what that is and how your trajectory led you to it?

It’s a position in the midst of all the accoutrements and traditions of the Anglican Church when leaders were trying to make decisions in the midst of their own culture wars, of accountability. It goes all the way back to Thomas Cranmer. So, the powers that be in the Church of England came up with this group that they call the “Six Preachers” who would hold the hierarchy, especially Canterbury Cathedral, accountable.

The number six is ambiguous in terms of what that actually meant. Some want to say it’s a sort of numerology for meaning “to be human,” or something like that. But I don’t think it was really a discrete number of preachers. You’re supposed to be there for a certain amount of time, and to be called back to set people straight, those who have gone astray, especially those leading folks back into the vision. You’re supposed to be that kind of voice that speaks clearly, prophetically, but also pastorally. It’s kind of a schizophrenic voice of being pastor and prophet.

As a Six Preacher, when Rowan Williams was the Archbishop [of Canterbury], he selected me. And this was very, very controversial: I’m from the United States and so on. A lot of the tensions in the Anglican Communion were not just on the global South; I think the British also had tensions with the Episcopal Church. I think one of the reasons that Rowan selected me was that I helped to start a course in the Anglican communion, where every summer we bring seminarians or newly-ordained folks from around the Anglican Communion [to Canterbury] for two or three weeks. I worked with a canon, Roger Simon, when I was initially in South Africa and coming back home from my stint with Archbishop Tutu, to create this course and it’s been going on since 1996 in Canterbury Cathedral.

Duke Divinity has struggled with retaining its African American professors, theologians, and students. Is there any advice you might offer to move forward from those challenges?

This is going to be a diplomatic response, but I’m hoping to say something honest. I want to applaud the Divinity School for having one of the first Black Church Studies programs, and for making a course in it a graduation requirement. At the time that I was teaching, it was one of the few programs to do so. As you know, the Divinity School has produced some pretty powerful theologians out of that program.

I think there almost needs to be a truth and reconciliation commission approach to conflicts, not just behind the scenes and in parking lot conversations, but publicly and maybe even theologically and liturgically. To talk about some of the past hurts, especially of some of the faculty, and the use of power that needs to be exorcised (like exorcising a demon!) to reveal how decisions were made. People who are doing theological education are no longer just coming out of college, and the pedagogy really has to work for those who have life experience. We need to figure out how to honor where those students are in their ministries, as well as having humility on both sides.

Author

Elizabeth Schrader

Ph.D. candidate, Religion

Elizabeth Schrader is fifth-year doctoral candidate in Early Christianity in Duke's Graduate Program in Religion. Her research interests focus on textual criticism, Mary Magdalene, the New Testament Gospels, and the Nag Hammadi corpus. She holds an M.A. and an S.T.M. from the General Theological Seminary. Follow her on Twitter.